Character Consolidation II

Character Consolidation

Part Two

Interactive Learning Module

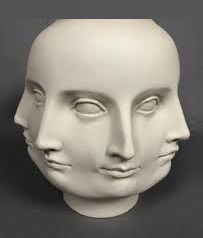

Multiple Faces / Fornasetti

1. Introduction

- לגרסה בעברית של יחידת לימוד זו, לחצו כאן.

- In Part I of this module we introduced the Midrashic technique of character consolidation in which various characters in Tanakh are identified one with another.

- We noted that the method might be employed to develop the identities of unknown figures, resolve exegetical questions, amplify the merits of the righteous and the faults of villainous figures, or show historical continuity.

- Often, to bolster their claims, Midrashim point to textual links and contextual parallels between stories.

- In this module, we will explore several more examples of the phenomenon, beginning with those which serve to mitigate apparent misdeeds of the Patriarchs.

2. Problematic Wives: "הַכְּנַעֲנִית"

- Access the Mikraot Gedolot on Bereshit 46:10 to see the list of Shimon's sons. What description is attached to the name of his last son? What does this imply about the ethnicity of Shimon's wife?

- Given Avraham and Yitzchak's efforts to ensure that their sons did not marry Canaanites and the later prohibition against such unions, how are we to understand Shimon's marriage?

- Scan Rashi (following Bereshit Rabbah) on the verse. With whom does he identify Shimon's Canaanite wife, thereby obviating the problem? Why is she called a "Canaanite"?

- What new halakhic issue does this suggestion raise? Why might this be less troubling of an issue to Rashi and the Midrash than the possibility that Shimon's wife was a Canaanite?

3. "The Canaanite": Ibn Ezra & Radak

- Rashi identifies Shimon's wife with Shimon's sister, Dinah, asserting that the marriage was an act of kindness, not a sin.

- In contrast, how does Ibn Ezra understand the word Canaanite? How does he evaluate the marriage?

- Now, look at Radak (accessible by pressing the "Show Additional Commentaries" button at the bottom of the verse). What middle position does he adopt?

- For further discussion, see Did Yaakov's Sons Marry Canaanites.

4. Problematic Wives: Asenat

- In contrast to Rashi, both Ibn Ezra and Radak suggest that Shimon did, in fact, marry a Canaanite. Ibn Ezra condemns the act, while Radak mitigates the wrongdoing by suggesting that this was only Shimon's second wife and the majority of his children were born by non-Canaanites.

- Other seemingly problematic wives are also provided with new identities by Midrashic sources. Turn to Bereshit 41:45 which describes Yosef's marriage to Asenat b. Poti Phera.

- According to Targum Yerushalmi (Yonatan) (accessible by clicking on the "Show Additional Commentaries" button), who is Asenat?

- What is likely motivating the identification?

5. Identity of Asenat: Pashtanim

- The suggestion that Asenat is none other than Dinah's daughter is likely motivated by discomfort with the possibility that Yosef would marry the daughter of an idolatrous priest.

- How does Rashbam reinterpret the verse to eliminate the difficulty without having to inject Dinah into the story?

- Why does Ibn Ezra reject Rashbam's interpretation? What alternative possibility does he raise that might similarly solve the problem?

- Ibn Ezra and Rashbam disagree regarding the meaning of the word "כֹּהֵן". Who is correct?

- Click on the word "כֹּהֵן" to access the One Click Concordance to see its usage throughout Tanakh. Must the root always refer to one who serves a deity, or can it also take the secondary meaning of civil servant? See also כֹּהֵן.

- To exit the concordance, click outside of the popup or on the corner x.

6. Explore Further

- Compare the above two examples with another case of apparent intermarriage, Moshe's marriage to the Cushite mentioned in Bemidbar 12:1. Who is this Cushite woman?

- What does Rashi, following the Sifre, suggest? Is this suggestion, too, motivated by a discomfort with Moshe's choice of partner? How, though, is this case different than the above examples?

- What other difficulties are raised by the identification?

- With whom, in contrast, does Rashbam identify the woman? What assumptions must his identification make?

- See Moshe and his Cushite Marriage for further discussion and other understandings.

7. Divine Providence: Princes and Officers

- An additional issue sometimes addressed via the consolidation of Biblical characters is that of Divine providence and reward and punishment

- Let's look at Bemidbar 7:2 which speaks of the princes who were privileged to dedicate the altar. With whom does Rashi (following the Sifre) associate them?

- What textual difficulty in the verse might be prompting this identification? What lesson might Rashi and the Midrash be attempting to convey through the association?

8. Officers and Elders

- Rashi and the Midrash associate the princes with the officers who had been whipped in Egypt, but it is not clear what message this identification is meant to impart.

- Let's turn to Rashi on Bemidbar 11:16 ("ה "אשר ידעת כי הם), where he makes a similar identification. Cf. the Sifre and Bemidbar Rabbah 11:16 ('אות כ), in "רש"י המפואר" (containing Rashi's sources, foils, and supercommentaries), accessible by clicking on the "ר" on top of Rashi's comment.

- With whom does Rashi identify the elders here? How might this bear on his earlier comments in Bemidbar 7? What textual clue is prompting the identification here?

9. Officers Rewarded

- Rashi identifies the elders, too, with the officers who had suffered in Egypt, motivated by the phrase: "אֲשֶׁר יָדַעְתָּ כִּי הֵם זִקְנֵי הָעָם וְשֹׁטְרָיו".

- Click on the word "וְשֹׁטְרָיו" in verse 16 to access the One Click Concordance. In what contexts do "שטרים" appear before Bemidbar 11? How might this support Rashi's identification?

- The linguistic connection notwithstanding, what do Rashi's final words, " עתה יתמנו בגדולתן כדרך שנצטערו בצרתם" suggest might be the ultimate goal of the identification?

- Is it problematic that in Bemidbar 7, Rashi identified the officers with just 12 individuals and here he connects them to 70 people? Does the double identification strengthen or weaken the suggestion?

10. Divine Providence: 400 Men

- The identification of the officers who suffered in Egypt with the elders and princes serves to demonstrate Hashem's providence, teaching the reader that the righteous who suffer are ultimately rewarded and compensated for their tribulations.

- A second more radical example of this motif might be found in Yalkut Shimoni on Shemuel I 30:17 (ד"ה ולא נמלט מהם), drawing off Bereshit Rabbah on Bereshit 33:16.

- With whom does the Midrash identify the 400 Amalekites who escaped David's sword? According to the Midrash, what had the original 400 men done to deserve reward? What in the text leads the Midrash to suggest this? [Compare Bereshit 33:1 and 16.]

- How is this example more extreme than the earlier one? Does the implausibility affect the message of the Midrash?

11. Hagar and Keturah

- Let's conclude by exploring a well-known Midrashic identification, that of Keturah with Hagar. This conflation appears to have been motivated by a combination of factors, including textual, exegetical, and moral issues.

- Access Bereshit 25:1 which describes Avraham's marriage to Keturah.

- Contrast Rashi, Rashbam, and Ibn Ezra's identifications of Keturah. How is each consistent with their general application or rejection of the principle of character consolidation?

- Scan the immediate context of the marriage (Bereshit 24:62-67 and Bereshit 25:1-11). What textual connections might be driving the identification of Keturah with Hagar? [See Tanchuma Chayei Sarah 8 who notes some of these.]

- To return to the Mikraot Gedolot, press here.

12. Late Marriage

- The context of this additional marriage of Avraham, which mentions Be'er LaChai Roi, Yishmael, and concubines, likely contributed to the identification of Keturah as Hagar, but other factors might have played a role as well.

- Our story is recorded after the death of Sarah, suggesting that Avraham was at least 137 when he remarried. What would lead him to marry again at such an advanced age?

- How might presenting Avraham as remarrying a previous wife rather than taking a new one mitigate the difficulty?

- In contrast, how does Shadal on Bereshit 25:1, deal with this issue? According to him, if the marriage took place earlier, why is it nonetheless recorded here?

13. Other Motivating Factors

- Two other issues might further contribute to the association of Keturah with Hagar.

- The Torah does not share that Avraham travelled outside of Canaan to find this third wife. In claiming that she is none other than Hagar, what other option might the Midrash be trying to avoid?

- Finally, how might Avraham's earlier discomfort with the banishment of Hagar (Bereshit 21:11-12) play into the identification? Might the Midrash be viewing the marriage as some sort of atonement for the expulsion?

- For further discussion of Avraham's marriage and the identification of Keturah, see Avraham's Many Wives.

14. Summary

- In this module we have seen several more examples of character consolidation and the different motivations which might have led to the various connections.

- Some identifications are driven by a desire to mitigate potential misdeeds of the Patriarchs, while others serve to demonstrate Divine providence. In our final example, the conflation of Hagar and Keturah, a variety of factors, from textual clues to exegetical and theological issues, may coalesce to contribute to the identification.

- In exploring the many examples, it is hard not to admire the ability of Midrashim to note nuanced parallels and ambiguities as they weave together characters over time and space to resolve exegetical or theological difficulties.

- By doing so, Midrashim often makes fascinating connections, creating a rich world in which Biblical figures take on more faces than a simple reading would allow.

- As such, the Midrashic method of character consolidation serves as an illuminating foil to more Peshat oriented approaches. It can enrich our study, helping us to think more deeply about the text, the questions it raises, and the messages it means to impart.

15. Additional Reading

- For further discussion and many more examples of this Midrashic technique, see: Character Consolidation.

- For more about Shimon's Canaanite wife, see: Did Yaakov's Sons Marry Canaanites.

- For discussion of Moshe's Cushite wife, see Moshe and his Cushite Marriage.

- For elaboration regarding the identity of Keturah, see Avraham's Many Wives.

- For other topics which touch on character consolidation not dicussed in this module, see Yitro – Names, and New King or Dynsaty.

- Return to the beginning of this module.

- Access additional Interactive Learning Modules.