Character Consolidation I

Character Consolidation

Part One

Interactive Learning Module

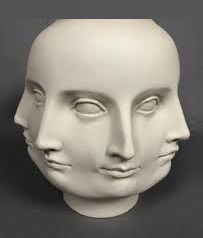

Multiple Faces / Fornasetti

1. Introduction

- לגרסה בעברית של יחידת לימוד זו, לחצו כאן.

- One of the techniques often employed by Midrash is the identification of different Biblical characters one with another, a method which can be termed the "Law of Conservation of Biblical Characters".

- In many cases, an anonymous or lesser known character (or even objects, places, and dates) is identified with a named and more famous figure. In other instances, two well-known personalities are identified as the same person.

- What drives this desire to consolidate Biblical figures? Why conflate two or more ostensibly distinct characters?

- This module will explore several examples of this phenomenon, in each case questioning what motivates the identification and how it affects our understanding of the narrative.

- Many examples and further discussion of the technique can be found at Character Consolidation.

2. Case I: Who is Yiskah?

- We'll begin by looking at an example where a named but unknown figure is identified with a more famous one.

- Access the Mikraot Gedolot on Bereshit 11 and scan verses 27-31 which provide background regarding Terach's sons, Avram (Avraham), Nachor, and Haran.

- Verse 29 records that Avram married Sarai, while Nachor married "Milkah, the daughter of Haran, the father of Milkah and Yiskah". Compare what the Torah tells us about Sarai's lineage with what it records about Milkah's. Can you account for the difference between them?

- Why does the Torah tell us the name of Milkah's father? Is there a relationship between this Haran (the father-in-law of Nachor) and the aforementioned Haran (the brother of Nachor)?

- Once the verse already noted that Milkah is the "daughter of Haran", why does it need to repeat that Haran is "the father of Milkah and Yiskah"? What must this be coming to teach us?

3. Yiskah is Sarah

- The phrase "אֲבִי מִלְכָּה וַאֲבִי יִסְכָּה" in verse 29 would be superfluous unless its point is to spotlight Yiskah. Who, though, is Yiskah and why does the verse find it important to mention her? Do we know her from elsewhere in Tanakh?

- Click on the name "יִסְכָּה" in verse 29 to access the One Click Concordance and see where else she appears in Tanakh. What do the results show? [To exit the concordance, click outside of the popup or on the corner x.]

- Our findings compound the question. As Yiskah appears nowhere else in Tanakh besides our verse, and apparently plays no role either here or later, why is she mentioned at all?

- On this backdrop, we can now better appreciate the comment of Rashi on verse 29 (following Bavli Megillah 14a). With whom does he identify Yiskah? How does this account for her inclusion in the story?

4. Questioning the Identification

- Rashi posits that Yiskah is merely another name for Sarah, thereby explaining her mention in the chapter.

- However, if Yiskah and Sarah are really one and the same, why refer to her by two names? How does Rashi attempt to address this question? Does his answer suffice?

- What assumption does the conflation of Sarah and Yiskah need to make about the identity of Haran, the father of Milkah?

- What third difficulty does Ibn Ezra note in the second sentence of his second commentary to verse 28?

5. Exegetical Motivations

- Given the textual difficulties mentioned above, it seems that the desire to identify Yiskah with a significant Biblical figure is not the only issue motivating the identification. As Shadal points out, exegetical factors also play a role.

- Let's turn to Bereshit 20. Scan the chapter for context and then focus on verse 12. How does Avraham describe Sarah when speaking to Avimelekh? Is there any prior evidence that Avraham and Sarah are related in this manner?

- How does identifying Yiskah with Sarah serve to verify Avraham's claim that Sarah is his "sister" (and not only his spouse)? What, though, is still difficult given Avraham's description of the relationship?

- How does R"Y Kara explain why Avraham refers to Sarah as "my sister, the daughter of my father", if she is really only his niece (as assumed by Rashi)?

6. Yiskah: Shadal's Position

- R"Y Kara points out that Tanakh is somewhat fluid in the terms used for relatives, and the word "אֲחֹתִי" might refer also to a niece or other relatives.

- Shadal, though, is still troubled by Avraham's reference to Sarah as specifically his sister, leading him to a different reading of the verse.

- According to him, how are Avraham and Sarah related?

- What would Shadal say about the identity of Yiskah?

7. Avot and Mitzvot

- Shadal suggests that Avraham's words should be understood literally, and that despite the earlier silence of the text, Avraham and Sarah were, in fact, half siblings, while Yiskah was a totally different person.

- What halakhic issue likely made Rashi reject Shadal's approach? How does Shadal respond?

- What assumption about the Patriarchs' observance of Torah law is each side making? See Avot and Mitzvot for further discussion of whether the Patriarchs observed the commandments.

- What other advantages might there be in positing that Avraham married his niece? How does Bavli Sanhedrin 76b evaluate such a marriage? Given Haran's death, why might Avraham's choice of wife be viewed as even more meritorious?

8. Yiskah: Ibn Ezra's Position

- Let's return to the Mikraot Gedolot on Bereshit 11 to see a third reading of our story. Ibn Ezra, like Shadal, rejects the identification of Yiskah with Sarah, but he explains Bereshit 20 differently.

- In his second commentary to Bereshit 11:28, how does Ibn Ezra explain Avraham's reply to Avimelekh?

- Why might Rashi be hesitant to adopt this reading of the story? Is it not problematic to suggest that Avraham might have lied?

- [See Ibn Ezra's first commentary on Bereshit 27:19 for other examples where he suggests that prophets might employ duplicity and how he justifies this.]

- According to both Ibn Ezra and Shadal, if Yiskah is not Sarah and plays no role in Torah, why is she mentioned at all? What does Shadal on Bereshit 11:29 suggest?

9. Case II: Datan and Aviram

- Let's move now to a second example of character consolidation, one in which a variety of anonymous characters found in several different stories in Tanakh are consistently identified by Midrashim as the same two known figures.

- Scan Rashi on Shemot 2:13-15, Shemot 5:20 and Shemot 16:20. With whom does Rashi identify the unnamed people in each verse?

- Earlier Midrashim precede Rashi in making these connections. Cf. Shemot Rabbah on 2:13 (regarding "שְׁנֵי אֲנָשִׁים עִבְרִים"), Shemot Rabbah on 5:20, and Shemot Rabbah on 16:20.

- What prompts the Midrashim and Rashi to consistently make this specific identification?

10. Textual Connections

- Rashi and the Midrashim identify Datan and Aviram as the individuals responsible for many wicked deeds, including: informing Paroh that Moshe killed the Egyptian, confronting Moshe after his failed negotiations with Paroh, and violating the prohibition of leaving over from the manna.

- In each case, linguistic parallels tie the stories to the rebellion of Datan and Aviram in Bemidbar 16.

- Go to Shemot 2:13 and click on the word "נִצִּים" to access the One Click Concordance. Where else in Torah does the word appear?

- Now, look at Rashi's comments to Shemot 5:20. What textual connection to the later rebellion does he draw here?

- Click on the word "נִצָּבִים" in the verse to access the concordance here as well. Is the word unique enough to support the identification?

- Finally, what parallel does Shemot Rabbah on 16:20 note? Is this word unique?

11. Fleshing Out Characters

- Rashi and the Midrash draw textual connections between the various stories in Shemot and the rebellion of Datan and Aviram, but not all of these seem strong enough on their own to warrant the identification.

- Is there some other common denominator between all four stories which might explain the choice?

- Let's access the library to see Tanchuma Shemot 10. With which other characters does the Midrash identify Datan and Aviram?

- What does the Midrash says these stories prove? What does this imply about the goal of the identifications?

12. Case III: Bilam

- By presenting Datan and Aviram as individuals with a history of animosity and rebellious actions, the Midrash fleshes out their character, providing background to understand Bemidbar 16. The resulting blackening of their character is further consistent with the Midrashic tendency to augment the faults of evil characters and amplify the merits of righteous figures.

- Let's now look at another example of the phenomenon, one in which the two figures who are equated are both known characters.

- See Targum Yerushalmi (Yonatan) on Bemidbar 22:5. [For an English translation, press the E in the upper corner.] Which two characters are being identified?

- Is there any exegetical difficulty which the identification is intended to address? What, then, is driving the Targum to conflate the characters?

13. Historical Continuity

- As there is no obvious exegetical difficulty and both Lavan and Bilam are known figures with developed personas, it seems, at first glance at least, that the identification is meant simply to exacerbate the evil character of Bilam.

- Why, though, might specifically Lavan have been chosen as Bilam's alter ego?

- What parallels exist between the two stories? [For some examples, see Bilam.]

- How is this example similar to the case of Datan and Aviram? Where, though, do the two differ? Are both identifications equally feasible?

- What is gained by identifying characters from different time periods? What statement about history is this type of Midrash making?

14. Explore Further

- The parallels between Bilam and Lavan serve to connect them, with the conflation of their identities serving to further blacken the character of each. This example, though, goes further than the earlier one, as it bridges historical periods, implying a continuity of anti-Semitism throughout the ages.

- To explore similar identifications, but of righteous figures, see the identification of Shifra and Puah with Yocheved and Miryam or Elisheva in Bavli Sotah 11a.

- How does this identification help develop the characters? How does it compare to the identification of the various rebels with Datan and Aviram? In this case, were there any other candidates to associate with Shifra and Puah? [For discussion, see Who are the Midwives].

- See also Targum Yerushalmi (Yonatan) on Shemot 6:18 and its identification of Pinechas and Eliyahu. How is this example similar to the identification of Bilam and Lavan? What parallels exist between the stories of the two zealots? What is served by identifying them as the same person?.

15. Summary

- We have explored several examples of character conflation, noting how the Midrash identifies anonymous, little known, and even famous figures one with another.

- In many cases the initial impetus stems from the Midrashic understanding that every word in Torah, and thus every figure, must be significant. Thus, through the technique, Midrash attempts to flesh out the identities of minor and unnamed characters who otherwise appear to play no notable role.

- At times, as in the case of Yiskah and Sarah, character consolidation serves to resolve exegetical difficulties. At other times, it contributes to character development, amplifying a figure's positive or negative traits.

- When people living centuries apart are identified, the technique also serves to bridge history, demonstrating continuity throughout the ages, somewhat similar to the concept of "מעשה אבות סימן לבנים".

- Often, textual connections or content parallels between stories play a role in the identifications, but these may be secondary to the above considerations.

- In Part II of this module, we will examine several more examples, seeing how the method addresses issues of Divine providence, apparent misdeeds of the Avot, and more.

16 . Additional Reading

- For further discussion of this topic, see: Character Consolidation.

- For Part Two of this module, see Part Two.

- Return to the beginning of this module.

- Access additional Interactive Learning Modules.